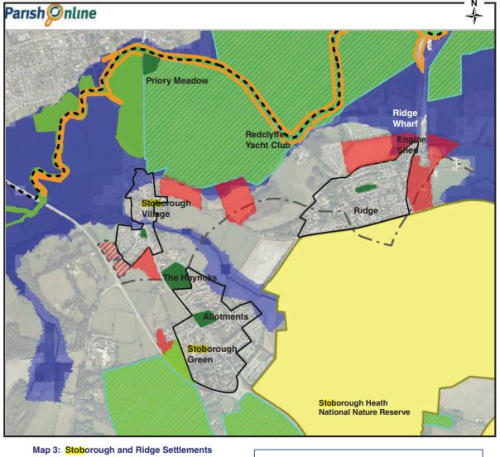

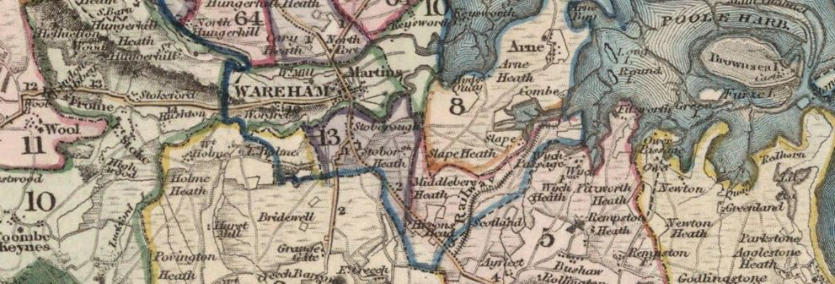

Stoborough Terms

Terms and Conditions

This website implies rights to honors, hereditments, intangibles and historical rights to related property around the world.

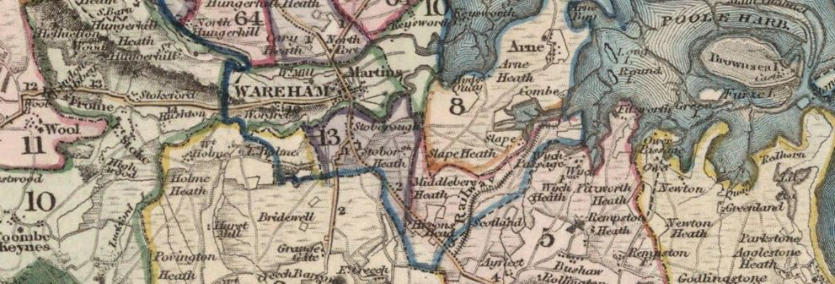

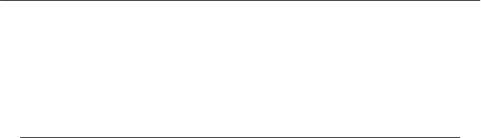

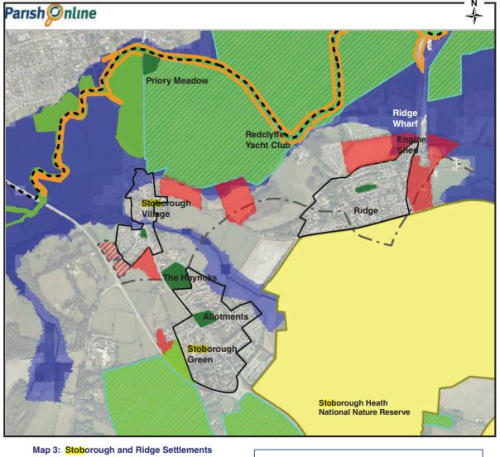

This site uses photos and likenesses of owners or rights holders. The website hasrights to use place names, ancient territory

names, rights to light, franchises, heretiments, land related intangible rights, images, copyrights,

This site is subject to the venue and jurisdiction of USA Colorado Federal Courts.

The lords and ladys of this seignory or territory may be several people including primary beneficiary, secondary beneficiary

and contingent beneficiaries.

Expenses of this research, seignory, property rights, marketing, branding, advertising, products, services, and other necessary

travel or publications are part of the company activities including the activities of honors holders: 1) Lady of Ennerdale 2)

Dame of Fief Blondel 3) Baroness of Longford and 4) Lady and Lord of Stoborough

Any unclaimed right is claimed herein to: Advowson or Patronage to existing or former churches, priories, abbeys or

cathedrals, any rights to tithes, any rights to common, any rights to foreshore on rivers and beaches, or lakes, rights to

commons of fishing and hunting, rights to commons of minerals, water, or elements, rights to estover and wood, rigts of ways

and servitudes, Offices, which are a right to exercise a public or private employment, and to the fees and emoluments

thereunto belonging, are also incorporeal hereditaments: whether public, as those of magistrates; or private, as of bailiffs,

receivers, and the like, Dignities, rights to Franchises, liberties, palatines, court leets, holding pleas, markets and fairs, forests,

chases, Free-warren, river water, lake water, ocean water, rocks reifs, ocean islands, inland islands, bays, waterways, boating

and water rights, rights to treasure, rights to mineral rights, landscape pictures, satellite images, Annuities, rents, or any honor

dignity or title related to former grants in relation to the lands or territories.

Forum, venue and Jurisdiction subject to the USA Federal Courts Colorado USA

WATER RIGHTS. By the law of England the property in the bed and water of a tidal river, as high as the tide ebbs and flows

at a medium spring tide, is presumed to be in the crown or as a franchise in a grantee of the crown, such as the lord of a manor,

or a district council, and to be extra-parochial. The bed and water of a non-tidal river are presumed to belong to the person

through whose land it flows, or, if it divide two properties, to the riparian proprietors, the rights of each extending to

midstream (ad medium filum aquae). In order to give riparian rights, the river must flow in a defined channel, or at least above

ground. The diminution of underground water collected by percolation, even though malicious, does not give a cause of action

to the owner of the land in which it collects, it being merely damnum sine injuria, though he is entitled to have it unpolluted

unless a right of pollution be gained against him by prescription. The right to draw water from another's well is an easement,

not a profit a prendre, and is therefore claimable by custom. As a general rule a riparian proprietor, whether on a tidal or a non-

tidal river, has full rights of user of his property. Most of the statute law will be found in the Sea Fisheries Acts 1843 to 1891,

and the Salmon and Freshwater Fisheries Acts 1861 to 1886. In certain cases the rights of the riparian proprietors are subject to

the intervening rights of other persons. These rights vary according as the river is navigable or not, or tidal or not. For

instance, all the riparian proprietors might combine 'to divert a non-navigable river, though one alone could not do so as

against the others, but no combination of riparian proprietors could defeat the right of the public to have a navigable river

maintained undiverted. We shall here consider shortly the rights enjoyed by, and the limitations XXVIII. 13 imposed upon,

riparian proprietors, in addition to those falling under the head of fishery or navigation. In these matters English law is in

substantial accordance with the law of other countries, most of the rules being deduced from Roman law. Perhaps the main

difference is that running water is in Roman law a res communis, like the air and the sea. In England, owing to the greater

value of river water for manufacturing and other purposes, it cannot be said to be common property, even though it may be

used for navigation. The effect of this difference is that certain rights, public in Roman law, such as mooring and unloading

cargo, bathing, drying nets, fishing for oysters, digging for sand, towing, &c., are only acquirable by prescription or custom in

England. By Roman law, a hut might lawfully be built on the shore of the sea or of a tidal river; in England such a building

would be a mere trespass. Preaching on the foreshore is not legal unless by custom or prescription (Llandudno Urban Council

v. Woods, 189 9, 2 Ch. 705). Nor may a fisherman who dredges for oysters appropriate a part of the foreshore for storing them

(Truro Corporation v. Rowe, 1902, 2 K.B. 709).

The right of use of the water of a natural stream cannot be better described than in the words of Lord Kingsdown in 1858: " By

the general law applicable to running streams, every riparian proprietor has a right to what may be called the ordinary use of

water flowing past his land - for instance, to the reasonable use of the water for domestic purposes and for his cattle, and this

without regard to the effect which such use may have in case of a deficiency upon proprietors lower down the stream. But,

further, he has a right to the use of it for any purpose, or what may be deemed the extraordinary use of it, provided he does not

thereby interfere with the rights of other proprietors, either above or below him. Subject to this condition, he may dam up a

stream for the purposes of a mill, or divert the water for the purpose of irrigation. But he has no right to intercept the regular

flow of the stream, if he thereby interferes with the lawful use of the water by other proprietors, and inflicts upon them a

sensible injury " (Miner v. Gilmour, 12 Moore's P.C. Cases, 156). The rights of riparian proprietors where the flow of water is

artificial rest on a different principle. As the artificial stream is made by a person for his own benefit, any right of another

person as a riparian proprietor does not arise at common law, as in the case of a natural stream, but must be established by

grant or prescription. If its origin be unknown the inference appears to be that riparian proprietors have the same rights as if

the stream had been a natural one (Baily v. Clark, 1902, 1 Ch. 649). The rights of a person not a riparian proprietor who uses

land abutting on a river or stream by the licence or grant of the riparian proprietor are not as full as though he were a riparian

proprietor, for he cannot be imposed as a riparian proprietor upon the other proprietors without their consent. The effect of this

appears to be that he is not entitled to sensibly affect their rights, even by the ordinary as distinguished from the extraordinary

use of the water. Even a riparian proprietor cannot divert the stream to a place outside his tenement and there use it for

purposes unconnected with the tenement (McCartney v. Londonderry & Lough Swilly Rly. Co., 1904, A.C. 301).

The limitations to which the right of the riparian proprietor is subject "may be divided into those existing by common right,

those imposed for public purposes, and those established against him by crown grant or by custom or prescription. Under the

first head comes the public right of navigation, of anchorage and fishery from boats (in tidal waters), and of taking shell-fish

(and probably other fish except royal fish) on the shore of tidal waters as far as any right of several fishery does not intervene.

Under the second head would fall the right of eminent domain by which the state takes riparian rights for public purposes,

compensating the proprietor, the restrictions upon the sporting rights of the proprietor, as by acts forbidding the taking of fish

in close time, and the Wild Birds Protection Acts, and the restrictions on the ground of public health, as by the Rivers Pollution

Act 1876 and the regulations of port sanitary authorities. The jurisdiction of the state over rivers in England may be exercised

by officers of the crown, as by commissioners of sewers or by the Board of Trade, under the Crown Lands Act 1866. A bridge

is erected and maintained by the county authorities, and the riparian proprietor must bear any inconvenience resulting from it.

An example of an adverse right by crown grant is a ferry or a port. The crown, moreover, as the guardian of the realm, has

jurisdiction to restrain the removal of the foreshore, the natural barrier of the sea, by its owner in case of apprehended danger

to the coast. The rights established against a riparian proprietor by private persons must as a rule be based on prescription or

custom, only on prescription where they are in the nature of profits a prendre. The public cannot claim such rights by

prescription, still less by custom. Among such rights are the right to land, to discharge cargo, to tow, to dry nets, to beach

boats, to take sand, shingle or water, to have a sea-wall maintained, to pollute the water (subject to the Rivers Pollution Act),

to water cattle, &c. In some cases the validity of local riparian customs has been recognized by the legislature. The right to

enter on lands adjoining tidal waters for the purpose of watching for and landing herrings, pilchards and other sea-fish was

confirmed to the fishermen of Somerset, Devon and Cornwall by I Jac. I. c. 23. Digging sand on the shore of tidal waters for

use as manure on the land was granted to the inhabitants of Devon and Cornwall by 7 Jac. I. c. 18. The public right of taking

or killing rabbits in the daytime on any sea bank or river bank in the county of Lincoln, so far as the tide extends, or within one

furlong of such bank, was preserved by the Larceny Act 1881. It should be noticed that rights of the public may be subject to

private rights. Where the river is navigable, although the right of navigation is common to the subjects of the realm, it may be

connected with a right to exclusive access to riparian land, the invasion of which may form the ground for legal proceedings

by the riparian proprietor (see Lyon v. The Fishmongers' Company, 1876, I A.C. 662). There is no common-law right of

support by subterranean water. A grant of land passes all watercourses, unless reserved to the grantor.

A freshwater lake appears to be governed by the same law as a non-tidal river, surface water being pars soli. The

preponderance of authority is in favour of the right of the riparian proprietors as against the crown. Most of the law will be

found in Bristow v. Cormican, 1878, 3 A.C. 648.

Unlawful and malicious injury to sea and river banks, towing paths, sluices, flood-gates, mill-dams, &c., or poisoning fish, is a

crime under the Malicious Damage Act 1861.

Ferry is a franchise created by grant or prescription. When created it is a highway of a special description, a monopoly to be

used only for the public advantage, so that the toll levied must be reasonable. The grantee may have an action or an injunction

for infringement of his rights by competition unless the infringement be by act of parliament. In Hopkins v. G.N. Ry. Co.,

1877, 2 Q.B.D. 224 (followed in Dibden v. Skirrow, 1907, I Ch. 437), it was held that the owner of a ferry cannot maintain an

action for loss of traffic caused by a new bridge or ferry made to provide for new traffic. Many ferries are now regulated by

local acts.

Weir, the gurges of Domesday, the kidellus of Magna Carta, as appurtenant to a fishery, is a nuisance at common law unless

granted by the crown before 1272. From the etymology of kidellus the weir was probably at first of wicker, later of timber or

stone. The owner of a several fishery in tidal waters cannot maintain his claim to a weir unless he can show a title going back

to Magna Carta. In private waters he must claim by grant or prescription. Numerous fishery acts from 25 Edw. III. st. 4, c. 4

deal with weirs, especially with regard to salmon fishery. An interesting case is Hanbury v. Jenkins, 1901, 2 Ch. 401, where it

was held that a grant of " wears " in the Usk by Henry VIII. in 1516 passed the bed of the river as well as the right of fishing.

Mill may be erected by any one, subject to local regulations and to his detaining the water no longer than is reasonably

necessary for the working of the wheel. But if a dam be put across running water, the erection of it can only be justified by

grant or prescription, or (in a manor) by manorial custom. On navigable rivers it must have existed before 1272. The owner of

it cannot pen up the water permanently so as to make a pond of it.

Bathing

The reported cases affect only sea-bathing, but Hall (p. 160) is of opinion that a right to bathe in private waters may exist by

prescription or custom. There is no common-law right to bathe in the sea or to place bathing-machines on the shore.

Prescription or custom is necessary to support a claim, whether .the foreshore is the property of the crown or of a private

owner (Brinckman v. Malley, 1904, 2 Ch. 313). Bathing in the sea or in rivers is now often regulated by the by-laws of a local

authority.

Scotland

The law of Scotland is in general accordance with that of England. One of the principal differences is that in Scotland, if a

charter state that the sea is the boundary of a grant, the foreshore is included in the grant, subject to the burden of crown rights

for public purposes. Persons engaged in the herring fishery off the coast of Scotland have, by II Geo. III. c. 31, the right to use

the shore for loo yds. from high-water mark for landing and drying nets, erecting huts and curing fish. By the Army Act 1881,

s. 143, soldiers on the march in Scotland pay only half toll at ferries. The right of ferry is one of the regalia minora acquirable

by prescriptive possession on a charter of barony. Sea-greens are private property. The right to take seaweed from another's

foreshore may be prescribed as a servitude. Interference with the free passage of salmon by abstraction of water to artificial

channels is restrainable by interdict (Pixie v. Earl of Kintore, 1906, A.C. 478). See the Salmon Fisheries (Scotland) Acts 1828

to 1868.

In Ireland the law is in general accordance with that of England. In R. v. Clinton, I.R. 4 C.L. 6, the Irish court went perhaps

beyond any English precedent in holding that to carry away drift seaweed from the foreshore is not larceny. The Rivers

Pollution Act 1876 was re-enacted for Ireland by the similar act of 1893.

In the United States the common law of England was originally the law, the state succeeding to the right of the crown. This

was no doubt sufficient in the thirteen original states, which are not traversed by rivers of the largest size, but was not

generally followed when it became obvious that new conditions, unknown in England, had arisen. Accordingly the soil of

navigable rivers, fresh or salt, and of lakes, is vested in the state, which has power to regulate navigation and impose tolls. The

admiralty jurisdiction of the United States extends to all public navigable rivers and lakes where commerce is carried on

between different states or with foreign nations (Genesee Chief v. Fitzhugh, 12 Howard's Rep. 443). And in a case decided in

1893 it was held that the open waters of the great lakes are " high seas " within the meaning of § 534 6 of the Revised Statutes

(U.S. v. Rodgers, 150 U.S. Rep. 249). A state may establish ferries and authorize dams. But if water from a dam overflow a

public highway, an indictable nuisance is caused. The right of eminent domain is exercised to a greater extent than in England

in the compulsory acquisition of sites for mills and the construction of levees or embankments, especially on the Mississippi.

In the drier country of the west and in the mining districts, the common law as to irrigation has had to be altered, and what was

called the. " Arid Region Doctrine " was gradually established. By it the first user of water has a right by priority of occupation

if he give notice to the public of an intention to appropriate, provided that he be competent to hold land.

Authorities

Hall's Essay on the Rights of the Crown on the SeaShore (1830) has been re-edited in 1875 and 1888. See also S. A. and H. S.

Moore, History and Law of Fisheries (1903). Among American authorities are the works of Angell, Gould and Pomeroy, on

Waters and Watercourses, Washburn on Easements, Angell on the Right of Property in Tide Waters, Kirney on Irrigation and

the Report to the Senate on Irrigation (1900). (J. W.)

Terms and Conditions

1. Introduction

Welcome to [Stoborough Manor], where we offer honorary lordships and manorial titles for sale. By purchasing and accepting

our titles, you agree to abide by the following terms and conditions.

2. Definitions

•

Title: Refers to the honorary lordship or any other title conferred by the company.

•

Company: Refers to [This Website and This Manor], its subsidiaries, and affiliates.

•

Customer: Refers to the individual purchasing or holding the title.

3. Purchase of Titles

•

Titles are for ceremonial purposes only and do not confer any legal or hereditary rights.

•

The purchase price is non-refundable once the title has been conferred.

4. Rights and Responsibilities

•

The title is granted for personal use only and cannot be transferred or sold to third parties.

•

Customers must uphold the dignity and decorum associated with the title.

5. Revocation of Titles

•

The company reserves the right to revoke any title at its sole discretion for any behavior deemed inappropriate or

damaging to the company’s reputation.

•

Reasons for revocation may include, but are not limited to, criminal activities, public misconduct, and actions that bring

disrepute to the title.

6. Intellectual Property

•

All titles, certificates, and associated materials are the intellectual property of the company.

•

Customers may not reproduce, distribute, or create derivative works from any materials provided by the company

without prior written consent.

•

Any negative commentary about the manor or lord would be deemed defamatory if not 100% truthful.

7. Limitation of Liability

•

The company is not liable for any damages arising from the purchase or use of the title.

•

The company does not guarantee the recognition of the title by any legal or governmental authority.

8. Privacy Policy

•

The company respects customer privacy and will handle personal information in accordance with our Privacy Policy.

9. Governing Law

•

These terms and conditions are governed by and construed in accordance with the laws of [Jurisdiction].

•

Any disputes arising from these terms and conditions shall be resolved in the courts of [Jurisdiction].

10. Amendments

•

The company reserves the right to amend these terms and conditions at any time. Any amendments will be posted on our

website and will take effect immediately.

By purchasing a title from [This Website and This Manor], you acknowledge that you have read, understood, and agree to be

bound by these terms and conditions.